Simon Sinek’s New Game

Simon Sinek’s new book takes on everything you think you know about business.

You may know Simon Sinek from his TED Talk — the third most popular of all time.

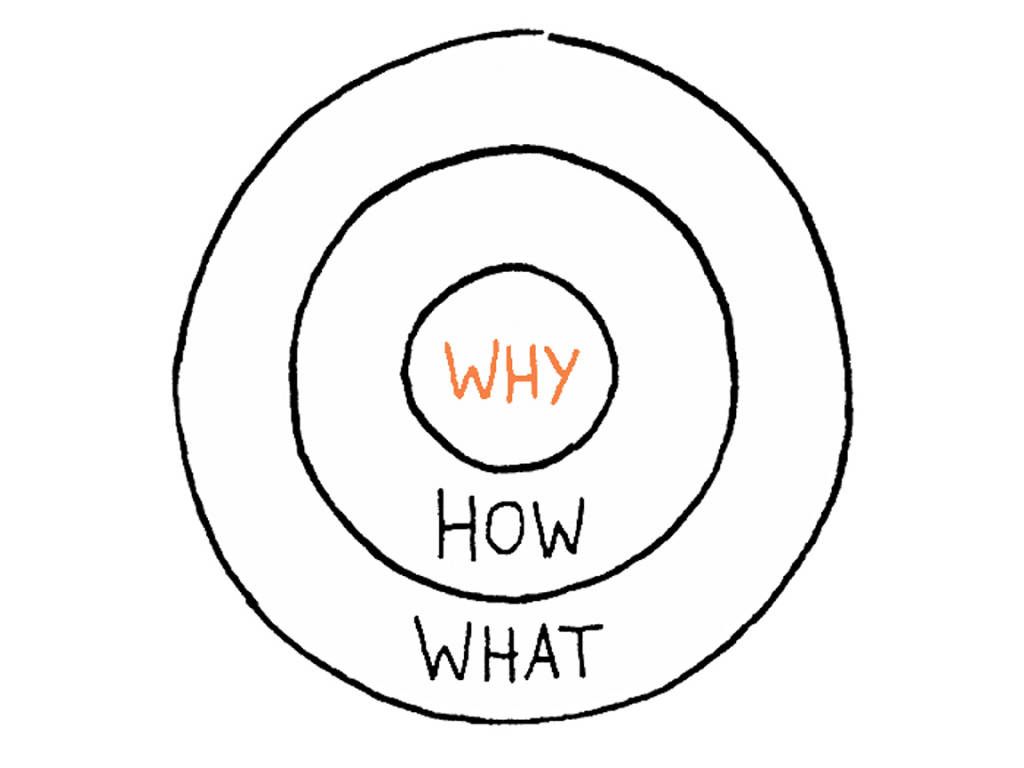

“People don’t buy what you do. They buy why you do it.” You may know Simon Sinek from his TED Talk — the third most popular of all time. Or you may know him from his best-selling books “Start with Why” and “Leaders Eat Last.” He’s built a career out of helping people find their “why.” He says — forget whether you’re seeking a mission, a purpose or a brand. It doesn’t matter what you call it. You need to figure out why you do what you do.

Now, Sinek is going beyond “why” to help leaders and organizations figure out how to navigate the future. Sinek’s newest book “The Infinite Game” challenges many conventional notions long-seen as foundational to business. He spoke to 360 Editor Chris Congdon from his home in New York to explain the difference between the finite and infinite game and why so many leaders get it wrong.

Chris Congdon: We use your concept of “why” often here at Steelcase. The idea is simple and elegant in its simplicity, yet it’s really hard. Why is that?

Simon Sinek: The reason why is a biological problem. The part of the brain that controls our behavior and controls our feelings is not the same part of the brain that controls language and analytical thought. When we try to analyze ourselves, we struggle to put the sense of why into words because the part of the brain that controls inspiration doesn’t control language.

We end up saying things like, “I know all the data says I should do this, but it just doesn’t feel right.” We talk about our guts guiding us. We talk about following our intuition. All of these weird things to say about making decisions, it’s actually that limbic part of the brain. It really takes another person to help you. It’s near impossible to do by yourself. You don’t have the objectivity you need to find the patterns in your life that reveal your why. I asked somebody to help me, and that’s what I like to do for others. I think the people who try to do it by themselves end up giving up.

CC: Where do organizations go wrong when they try to find their why?

SS: When organizations go through this process, it’s often a process of consensus. They interview everybody in the organization. The problem is, it gets very diluted. The two best ways to do it are to go to the founder leader, if that person is still alive. The organization is a representation of who they are. It was born out of them and their personality. Virgin is Richard Branson. Apple is Steve Jobs. Star Wars and Lucas Film is George Lucas. They’re inseparable. The culture was formed around the person.

If you do not have a founder leader who’s still available, go to the zealots. The people who are emotionally connected and would never leave. They love this place. Gather a cross-section. All job functions, all ranks. I want the people who really love it here. Because that commonality of what they love is the why.

At its core essence, why is an origin story. It can apply at a macro level for an organization. And it can apply at a micro level for a product. Everything we make, everything we do needs a reason to exist. It has to be born out of some problems, and needs, some personal experience. Those are always the best, most authentic things that exist in the market.

CC: Your new book is about this idea of an infinite game. What took you down this path?

SS: The original articulation of what a finite game and an infinite game is was introduced by a theologian by the name of James Carse in the 1980s. He proposed that if you have at least one competitor, you have a game and there are two types of games. There are finite games and there are infinite games.

The finite game is composed of known players, fixed rules, and an agreed upon objective. Baseball or soccer, we agree on the rules there. We play by the rules, at the end we declare a winner and the game is over. There’s beginning, middle and end. An infinite game is defined as known and unknown players. The rules are changeable, and the objective is to stay in the game as long as possible.

There’s no such thing as winning in an infinite game. When I learned about this and as I took a look around the world, I realized how many infinite games we are always players within. There’s no such thing as winning in marriage. There’s no such thing as winning in friendship. There’s no such thing as winning in global politics. There’s definitely no such thing as winning business.

You have wins in business, but there’s no winning business. It’s an infinite game. The players come and go. You might go bankrupt, a new company may be formed, but the game continues without you. It occurred to me that if we are players in these infinite games, the vast majority of leaders, if you just listen to their language, don’t actually know the game that they’re in.

They talk about being number one. They talk about being the best. And they talk about beating their competition. All of which are impossible. What I learned is that if you play with a finite mindset, in other words, trying to be number one, to beat your competition, in an infinite game there are few very consistent and predictable outcomes including the decline of trust, the decline of cooperation and the decline of innovation.

CC: Having a competitor can be pretty motivating. What’s wrong with wanting to beat the competition?

SS: The problem with the word competitor is it sets up the wrong dynamic. We have competitors in a race. The idea of competition is to win. We set out to beat our competition. It is absolutely unbelievably motivating. The problem is, the metrics we choose, and the timeframes we choose are arbitrary. Usually we choose a year because that’s when we pay taxes. Could be we look at quarterly earnings. We get to choose the numbers as well. Is it revenue? Market share? Profitability? Earnings per share? The number of employees you have? You can choose any metric you want and claim you are the winner. And so the problem is, when we become too fixated on beating our competition, sometimes we make reactionary decisions.

It doesn’t actually advance innovation because we’re looking to react to what they’re doing rather than advance a cause or something bigger than ourselves. If you are number one, then it puts you in an entirely defensive posture, where you’re now trying to protect your position. Which definitely hurts innovation.

A healthier way to think about competition in the infinite game is to think of worthy rivalries. Another organization or player that is in the game and is worthy of comparison. That player is as good or better than you at some or many of the things you do, so they become a benchmark. You absolutely do push yourself to improve, but the only true competitor in an infinite game is yourself.

“There are a few very predictable outcomes when you play with a finite mindset, including the decline of trust, cooperation and innovation.”

CC: You talk in your book about needing a “just cause.” Is a “just cause” linked to your “why”?

SS: They’re definitely linked, but they’re different. A “why” comes from the past. It is the foundation of the house. Whereas a just cause is a vision of the future, so far into the future, so idealized we will never actually get there, but we will die trying. A just cause is what gives our life and our work meaning.

The United States declared it’s just cause in the Declaration of Independence. All men are created equal, endowed with certain unalienable rights amongst which include life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. And we set out to build a nation that would embody these ideals. And we’ve seen the nation try. We’ve seen it with the abolition of slavery and women’s suffrage, and civil rights and gay rights and we’re still stumbling our way. We’re still not there, even with those things all the way. You can see that the nation is trying to deliver on the ideal.

Organizations can have a just cause. Sometimes it’s called a vision. There’s constant debate. What comes first? Vision or mission? Who cares? Some say it’s brand. Some say it’s purpose. There’s too much debate as to what the words are. Let’s agree that it’s a “just cause.” A cause so just we would be willing to sacrifice to advance it. Work late. Go on frequent business trips, all of that.

CC: It’s very common in business to hear that the reason we exist as a company is to return value our shareholders—our investors. As an adult, I have a few investments of my own. Why is that not a just cause?

SS: Money is not a cause. Money is a result. That definition is largely based on the work of Milton Friedman, the Nobel Prize winning economist, who in the 1970s theorized that the purpose of business is to maximize profits within the bounds of the law. This notion of shareholder supremacy was fully embraced in the ’80s and ’90s.

The problem is, it takes a very, very simplistic view of business that money is the only thing that matters. Business is more dynamic than that. There are human beings involved. There are human beings in the making of the products, in the making of the companies, in the buying of these things. And to simply maximize profit, leads to some rather unethical behavior. Milton Friedman said “to maximize profit within the bounds of the law.” What about ethics? Ethics is a much higher standard than the law.

There are two currencies in the infinite game—will and resources. In the finite game, the finite-minded players, there’s only one currency, which is resources to maximize profit. Of course, money is important. Without money, you don’t stay in the game. The infinite game considers the importance of human beings and the dynamic of business which Milton Friedman did not.

CC: You write about this idea of needing a “courageous leader” in the infinite game. What does that mean versus someone who is just achieving their goals?

SS: So many of the pressures we face at work every day push us to play with a finite mindset. Many of our incentives at work, are based on arbitrary financial goals, set on arbitrary dates, by people more senior than us in the organization.

There’s this assumption that some of the accepted business practices are actually the right way to run a business. It’s unbelievably difficult and it takes unbelievable courage to say, “We reject Milton Friedman. We reject short-termism. We reject the notion that this is how business works. And we’re going to run our business the way we think a business should run.”

Having a just cause, a reason that’s bigger than making money, is actually a good way to run a business. In fact, it’s a better way to run a business. It’s the courage to do the right thing. It’s the courage to march to the beat of your own drum. It’s the courage to put your cause before everything else. It’s the courage to run the business highly ethically, even if it may cost money in the short-term because it’s the right thing to do.

Companies that do these things actually outperform the other companies over the course of time. I’ve never met a CEO on the planet who’s said people aren’t important. But, then, look at the way they actually make decisions. They utilize layoffs to make the numbers and meet their arbitrary projections. Some companies use layoffs even when they’re profitable. It’s just they weren’t as profitable as they predicted. There’s something unbelievably uncomfortable and wrong with using someone’s livelihood to demonstrate they made the right arbitrary projection. This is not about trying to save a sinking ship. This is not about using layoffs when facing bankruptcy.

Good old fashioned leadership creates trusting teams. It’s where we recognize leadership is not about being in charge, but about taking care of those in our charge. Leadership is not an event. It’s not a class. It is a skill and it is a lifestyle. Like being healthy. You don’t go to the gym simply to make your weight and then stop going to the gym. Even if you hit your goal, you still have to keep going to the gym for the rest of your life. Parenting is a lifestyle. It’s not do you want to have children? It’s, do you want the lifestyle of being a parent? Leadership is the same. It’s all fine and good to say, “Yes, of course it’s important for our people to trust each other.” But, the leaders are actually responsible for creating the environments in which trust can exist. That idea is a lifestyle too many leaders do not embrace.

CC: Your book also covers this idea of needing to be more responsive to the conditions of the game as they change. What kind of advice do you give here?

SS: I call it existential flexibility. It’s the willingness to make a profound shift in strategy to advance your cause. This is not about the daily flexibilities of doing business. This is about the willingness to completely change your business model because you see that the path you’re on is no longer viable. For example, why is it that a computer company came up with iTunes and not the music industry? Why is it that a new startup came up with Netflix and not the movie or TV industry? Why is it that that Amazon invented Amazon and the e-reader, not publishers? That’s screwed up.

It’s because they were protecting their existing business model. And despite the fact that new technology was coming, they didn’t want to adapt because it would have been too painful to their business models. They waited until they were forced to.

Here’s one of my favorite examples. When Netflix started, they had this new business model of subscription, even though streaming technology wasn’t quite good enough yet, you could see it was coming. Blockbuster’s CEO at the time, and blockbuster was the 800 pound gorilla, went to see the board and said, “We need to change the business model to include subscriptions.” The board said, “No.” Do you want to know why? Because the company made 12% of its revenues from late fees. If you’re not willing to blow up your own company, then the market will blow it up for you.

“Having a just cause, a reason that’s bigger than making money, is actually a good way to run a business.”

CC: We’re seeing a real macro shift to a fast-paced style of team-based work to help companies innovate and grow. That takes a lot of trust to be vulnerable and share your ideas even when they are fragile. What are conditions organizations could embrace to help build more trust?

SS: You know you have trusting teams when the people on the team feel psychologically safe enough to say, “I made a mistake,” or, “I’m struggling at home and it’s affecting my work,” or, “You’ve promoted me to a position, and I don’t know what I’m doing. I need more training.” Or, “I’m scared, or I need help,” without any fear of humiliation or retribution.

It is hard to do. If a leader is not committed to creating an environment for trusting teams, you have a group of people who are showing up to work every single day, lying, hiding, and faking. They’re hiding their mistakes. They’re pretending they know how to do things they don’t. They’re never going to tell you they need help. And over the course of time, things will break.

At the end of the day, we are social animals and we need each other. We’re better together. We’re no good by ourselves. In those conditions, that environment must be set by the leader. Which means it’s much like having children. You don’t get to choose your children. And sometimes you don’t get to choose your team. And regardless of who your children are, and regardless of who your team is, you have to trust them, and you have to love them. It drives me nuts when leaders say, “You have to earn my trust.” No, it’s the complete opposite. You have to earn their trust, to do that, you must trust first. That is one of the conditions of leadership. The people are not required to trust you, you are required to trust them. And you must earn their trust. When we work to create an environment in which people feel psychologically safe to be themselves, the result is teamwork so powerful, so compelling, we literally love our teammates.

CC: Because the physical environment begins to tell you something about who a company is and what they value, I’m curious how you would describe the perfect environment for the players of an infinite game?

SS: It’s an impossible question because it will be different for every company. You have to know who you are. You have to know your “why.” You have to know where you’re going and what you actually believe. Just like people want to be themselves. Companies have to be themselves as well.

The office environment has to reflect their personality. I went to an office just recently and it was the most generic, boring environment I’ve ever seen. There was nothing that reflected who they were. I met them. They’re lovely people. They’re dynamic. Then I walked through their offices, and it was like they just spent a ton of money in generic expensive furniture. It was just like a TV studio office. It was boring.

Then, you visit Southwest Airlines and it feels like what you would expect it to feel like. There’s pictures of people on the wall, and everything’s pretty. When you go into the executive officers, they look exactly like all the other offices. It’s very egalitarian. You’re walking around and go, “Yeah, this is exactly what I expected.” You go visit Apple’s headquarters and it all looks like apple products. All of the edges and corners are the exact same angle as your iPhone or your iPad. It’s amazing. It feels like exactly how you would expect it to feel.

Hear more from Simon Sinek by visiting our What Workers Want podcast archives.