A New Legal Brief

As the legal industry evolves, its work environments require new approaches.

As the legal industry evolves, its work environments require new approaches.

As a nation of laws, the U.S. has always depended on its lawyers. But today the legal industry is perhaps more important than ever before to a country with the world’s largest gross domestic product, most patent filings, most new business start-ups, and the most watched, emulated, and successful of economies. The global nature of business involves legal issues ranging from intellectual property, patents, and trademarks, to venture capital, mergers and acquisitions, energy, the environment, and international law.

To meet this challenge, the legal industry itself is changing:

- More Large, global firms – a growth in the number of large law firms as international corporate clients require more legal services

- More Collaboration – the essential method of knowledge work today, collaboration, is central to more legal processes and work spaces

- New Pressures – trends affecting every business, from the rising cost of real estate to the growing diversity of workers, are also affecting law firms, their work processes and environments

- Digital Technology – the legal process still includes towering mounds of papers, but firms are increasingly adopting digital tools

- Changing Priorities – lawyers today seek a better work/life balance, so law firms are offering new positions and incentives to attract and retain talent

These changes hit home in the law office. New ways of working require new approaches to the design and planning of law space, so Steelcase took an extensive look at the legal industry, conducted primary research and developed new strategies for legal workspaces. This paper offers an overview of the research, examines the work processes and behaviors of the legal industry, and offers new workplace strategies to help law firms adapt to a changing business world.

Lawyers at Work

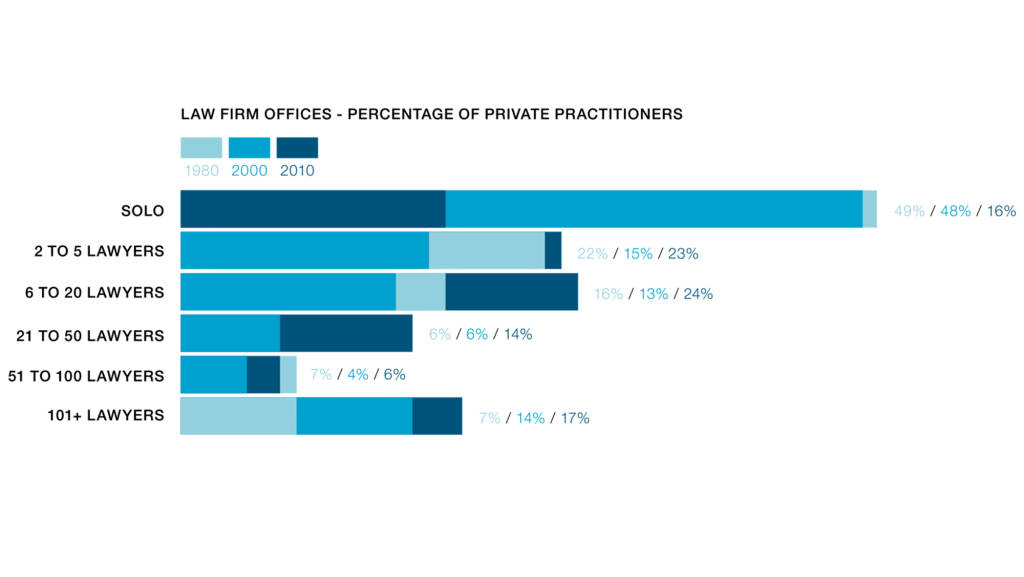

The majority of the nation’s nearly 1.2 million lawyers work in private practice, many as solo practitioners or in small firms with fewer than a half-dozen lawyers. Others work in the growing number of “super size” firms with hundreds of lawyers and offices located around the world, providing expertise and services to multinational clients. In fact, the number of firms staffed with more than 100 lawyers doubled between 1980 and 2000, and just since the mid-90s, at least one-third of attorney positions have been with these largest firms. As of 2008, 43.2% of all law firm jobs were with firms of more than a hundred lawyers.1

The super-sizing of law firms is the result of a global economy that has produced large, often international companies who require a diverse range of legal services. These clients desire law firms that can handle all their legal needs, so law firms are getting bigger and adding expertise their clients demand, often through practice consolidations. Large law firms are growing by hiring more specialists, and many regional firms are finding that they too must expand to keep up with customer requirements. Mergers among midsize law firms also have increased.2

Larger firms (colloquially called “biglaw” or “megafirms”) tend to include lawyers with expertise in specialized areas such as intellectual property, mergers and acquisitions, etc. These firms organize in traditional functional groups, or in teams that handle large, complicated issues for their client companies. As a result, traditional one-on-one attorney/client meetings have been replaced by collaborative group meetings of client and legal teams. Standards programs have changed, too. Private offices are typically smaller, and rarely are customized for individuals. Shared offices have increased in number, and many enclosed offices have been designed as multifunctional spaces that can function as either private offices or meeting spaces.

How firms use space has changed, as many law firms have become less hierarchical and younger attorneys have entered the industry. Private offices are still prominent features of law firms, of course, but they are used less frequently as performance rewards. Shifting generational attitudes are one reason; turnover is another. Traditionally, lawyers joined firms as associates and worked to become one of the joint owners and directors of the firm, or partners. It’s increasingly common now for associates to join a firm to gain experience and a healthy salary with no thought of achieving partnership status then move on after a few years. In fact, 78% of associates leave law firms by their fifth year.3 To retain top performers, some firms offer non-equity partnerships with titles such as “of counsel” or “special counsel.” Many firms have introduced other incentives such as mentoring programs, work-life balance initiatives, and flexible hours.

All private practice lawyers, on the partner track or not, are driven by the same need to generate billable hours, just like architects, designers, and engineers. Billable time is often tracked down to six-minute increments, a measure of the importance of generating revenue for the firm while providing clients with advice and counsel.

Recently, in response to more cost-conscious clients, the industry has struggled to find alternatives to the billable hour model. Though it’s not a widespread trend, some firms are negotiating flat fees for handling certain work, success fees for positive outcomes, and payments for meeting agreed upon benchmarks such as settling a case for less than the client feared having to pay if it lost in court.4 Many smaller firms and solo attorneys have long performed basic legal services, such as drawing up simple wills and trusts for flat fees, and plaintiff lawyers often work on a contingency basis. But pricing complicated legal work is difficult, and when the recession ends, so too may the push for alternatives to hourly billing.

Paralegals: More power of attorney

The two primary types of private legal practice, transactional law and litigation law, operate differently. Transactional lawyers, who are usually associated with corporate law and contracts, have many more cases at a time, but their files tend to be smaller. In contrast, litigation lawyers, who work on civil and criminal cases, tend to have fewer active cases but require more room to support them as multiple people sift through documents (print or electronic) to find key information, evidence, or the legal precedent that will solve a case.

There are four primary players in the law firm.

- Partners are the senior lawyers. They are typically joint owners who make policy decisions for the firm. They own the client relationship.

- Associates are lawyers that work directly under the partners; many of them aim to become partners.

- Paralegals are law professionals with legal training, but they are not lawyers. They work under the supervision of the partner or associate. Patent engineers are typically included in this group.

- Legal assistants are administrative staff for attorneys and the consolidation point for the legal team.

(Note: the terms “paralegal” and “legal assistant” have traditionally been considered synonymous. Court rules, statutes, and bar association guidelines define them as the same job. However, in recent years, firms have allowed file clerks, secretaries and others to use the term legal assistant. Paralegals increasingly prefer the more professional and independent title of paralegal, and it helps avoid confusion, so this paper has adopted the more current distinction between paralegals and legal assistants.)

Megafirms also include operating officers and facilities managers, who are often on the management team. These MBA-trained executives bring a more corporate approach to their real estate and workplace strategies. Support staff at medium to large firms often includes mail clerks, document clerks, and graphic design professionals.

Paralegals are in high demand, and job growth is projected to be twice as fast as for attorneys.

One major change in law firm staffing in recent years has been the rise of paralegals. They can perform a variety of legal tasks for lower salaries than those of attorneys, allowing firms to thin attorney ranks and fill the gaps with the specialized skills of paralegals.

Paralegals are prohibited from work considered law practice, such as giving legal advice and presenting cases in court, but they perform many critical tasks once performed solely by attorneys: preparing for closings, trials, and hearings; analyzing and organizing information; helping to prepare legal documents; and organizing and tracking case documents. This combination of flexibility and lower cost puts paralegals in high demand. In fact, paralegal employment is projected to grow 22% between 2006 and 2016, much faster than average for all occupations, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and twice as fast as attorney employment is expected to grow.5

The rise of paralegals is indicative of changing staff ratios in the four primary positions of law firms. A few years ago, it was common to have a one-to-one ratio of lawyers to legal assistants, just as corporations used to have one administrative assistant for each manager. Today, one legal assistant typically supports three to four lawyers, and Steelcase researchers found assistant-to-attorney ratios as high as 6 to 1 when law firms pool assistants.

One attorney may work closely with one paralegal, or as many as eight to ten. The number of associates varies inversely to the number of paralegals. More complicated cases translate into more partners and associates (about 2 to 4 for each partner) and fewer paralegals.

These changing ratios dramatically affect the firm’s real estate. It’s not unusual to find vast, empty spaces in open plan areas originally designed for bygone staffing ratios, along with increased internal travel distances, and an obvious need to rethink adjacencies between attorneys and staff.

An additional planning consideration is outsourcing. Some firms outsource litigation support work, such as scanning, coding, and document review, legal research, and the creation of routine legal documents. Whether the outsourcing is to an offsite vendor or to an onsite, temporary contract worker, there are implications for the space plan and its ability to quickly adapt to changing work processes and staffing levels.

Different industry, same pressures

Economic and social changes buffeting other industries have reached the marbled halls of the legal profession. The economic decline of 2008 affected law firms, as average profits per partner and revenue per lawyer dipped among the nation’s top-grossing firms for the first time since 1991, with another decline in 2009.6 That led to record law firm layoffs last year, and a sequence many other businesses shared: a squeeze on revenue and profits driving the need to cut costs and staff, followed by the desire to consolidate real estate, fine tune work processes, and reconsider workspace needs.

At the same time, shifting worker attitudes about work/life balance, and Gen Y workers with new ways of thinking about work and careers, have made it harder for law firms to retain highly educated, experienced talent. For example, a San Francisco-based law firm with Fortune 500 clients announced in March 2009 that it would pay associates a full year’s salary if they left the firm and worked at an approved charity or legal-services organization for a year. Other law firms offered similar deals for pro bono work, leaves of absence, and sabbaticals.

The legal industry also has its own retention issue, called “lateral lawyering,” the phenomenon of lawyers changing jobs, unworried about striving for partnership status. Research shows these lawyers move on for one of five key reasons: the need for professional development, practice interests, financial incentives, the workplace environment, and work/life balance.7 Lateral lawyering causes firms to worry about breaks in continuity and its impact on client relations and the talent pipeline.

Law and Order: The unique needs of the legal workplace

Law firm work processes have several similarities with other professional services firms, and a few peculiarities. For starters, workflow in a law firm doesn’t follow a linear course. Just as in an ad agency or a design firm, content generation and manipulation is often a random process. Keeping a variety of materials both physically and visually available to legal workers is vital to their work process.

Visible information provides legal professionals with memory triggers.

The Legal Industry – by the numbers

– Annual revenue of the U.S. legal industry: $180 billion8

– Number of law firms in North America with 100 employees (40+ attorneys) or more: 1,3549

– Number of those firms with 250 employees or more (100+ attorneys): 375

– Percentage of full time lawyers who work 50 or more hours per week: 3710

– Median salary for a private practice lawyer, 9 months after graduation: $85,000

– Average debt among lawyers who joined the bar in 2000: $70,00011

– Median salary (2006) for lawyers: $102,000

– Median salary (2006) for paralegals and legal assistants: $43,000

The partner, the lead attorney who manages the legal team on the case, performs independent work that is then shared in a collaborative manner. Work migrates over the course of a day, week, month or even year, between private offices, case rooms, conference spaces, litigation venues, and courtrooms.

All of this coordination involves the examination and movement of large amounts of both paper and electronic documents as workers search to find the “golden nugget” that will break a case. The random nature of the process and its dependence on paper makes it unlikely the work will migrate toward more at-home work. Legal firms will continue to need a central location to support collaboration and document movement and sifting.

Current work and anticipated work must be kept visible, since each day multiple projects are tackled and more information is added to each case or client folder. Filing becomes inefficient and detrimental to work process: it takes away from billable minutes, eliminates “visual triggers” to projects/cases, and hides opportunities to connect pieces of data.

Computers play less of a starring role in the legal industry than in any other industry Steelcase has studied.

Partners, associates, paralegals, and administrative workers all have specific workspace needs based on their role. For example, associates spend much time cross-referencing paper and electronic sources, and meeting informally with different types of people. A partner, meanwhile, performs focused work, reviews work done by others, and directs and mentors individuals. each of these partners tends to create physical zones within their workspaces (often located in private offices to encourage concentration) for different types of work and the different stages of its path to completion. Information must be visible to provide memory triggers. If a file is pending incoming information, it will go in a designated “hold” pile within the office. As priorities shift, work is rescheduled and work processes are adjusted. It happens so frequently that list making is ineffective; it’s more efficient for the actual file to act as the item on the list.

File folders often have top sheets to designate the folder’s status. The folders are frequently arranged and rearranged in a cascading way to help get the professional into “flow” faster. As projects move from one stage of completion to another, their designated location in an office may also change. For example, if a case is ready to be closed, but may still have a few closing items that need to be added to it in the next month, it will move farther away from the core work area. Most cases start out in manila folders and end up in Redweld®-style accordion folders, and eventually in a banker’s box as the case progresses.

The Paper Chase

The law profession remains a very paper-dependent industry. Computers play less of a starring role in the legal industry than in most other industries Steelcase has studied. Paper rules here because of the massive amount of cross-referencing that occurs, and because technology hasn’t been adopted in this industry as extensively as in others. There are several reasons for this behind-the-curve status, including huge concerns about the confidentiality of digital information handling and storage, regulations requiring paper copies, and the industry’s cautious approach to change. While more law firms are exploring digital means of information storage, an American Bar Association survey reports that less than half of attorneys (47%) have online storage available at their firms.12

The legal industry’s paper usage presents unique storage needs. Most industries use 8-1/2”x11” paper and matching hanging folders, but many in this industry use legal-length (14”) paper, over-sized manila folders, Redweld® folders, and banker’s boxes. Unfortunately, most of these don’t fit into standard file drawers or overhead storage units. If they do fit a file drawer, they can’t easily be labeled for identification. Storage items sit on the bottom of file drawers that are typically not designed to carry massive weight. This leads to warped or broken file drawer bottoms. In either case, worker frustration grows.

Managing these massive amounts of paper documents, even just physically moving them around, is a complex and time-consuming process. Files, boxes, and folders regularly circulate between private offices, case rooms, aisles and storage areas, creating tracking nightmares.

In most businesses, storage is split between active, anticipated and archived categories. In the legal industry, archive materials take up a very large percentage of storage. Computers are changing this somewhat, but slowly. Many law firm staffers only have one monitor, for example. Since many documents are frequently cross-referenced, and since they deal with huge amounts of information, legal workers often find it easier to print documents while working on cases. This leads to even more paper documents piled or stored as anticipated and archive material.

Planning the new law office

To address the changing needs of the legal industry, law office planners and designers might consider several strategies developed by Steelcase and based on its research of the legal industry. In some cases, illustrations are offered to demonstrate these workplace strategies in applications.

Law firms are moving away from large partner offices with furniture allowances that in effect create single-office furniture standards. Instead, partners are receiving furniture selected from standardized options. By planning smaller offices in standard sizes across job types to give the firm greater flexibility to easily adapt real estate, a partner office can be changed into an associate office, a conference room, or a dedicated case room when the need arises.

Another pillar of law firm tradition, law libraries, are shrinking or disappearing. Most research is now conducted online (the ABA says 96% of attorneys conduct legal research this way13). The library is now frequently located near the lobby to be used as a client meeting space that also makes a statement about the brand and culture of the law firm. Many firms have become more aware of their brand image in the market in recent years. As a result, more firms are moving away from old-fashioned dark woods and paneling to a more progressive aesthetic with lighter colors and materials and a contemporary look. It’s an attractive look to both a new generation of lawyers and the firm’s clients. This is especially apparent in an increase in more client-facing spaces, such as libraries/client conference centers, and small meeting spaces adjacent to the firm’s entrance. These spaces offer the added benefits of keeping clients out of chaotic staff areas and helping to preserve the confidentiality of exposed files.

Collaboration – between law firm workers, and between lawyers and their clients – needs appropriate attention in any law firm. Teams of legal professionals regularly work in concert with colleagues as well as clients. Partners, associates, and paralegals, as well as administrative staff, still perform focused, individual tasks, of course, but they also meet informally many times throughout the day. This collaboration occurs in private offices, conference and case rooms, libraries, and in the open plan. As a result, law firms need a variety of collaborative spaces. Many private spaces (partner offices especially) also require space for one-on-one and small group discussions. This allows individuals to switch quickly from focused work to group work. For example, two or three individuals may need to view content on a computer screen. Meanwhile, informal meetings occur in the open space and short conversations happen on the periphery of the workspace at stand-up and lounge spaces designed for easy collaboration.

A more global, mobile law profession also needs ways to collaborate across distances. Videoconferencing (called telepresence at the high-definition level) is being adopted by many firms as a way to gather dispersed staffers for firm-wide meetings and training sessions, and to “meet” with partners and clients while reducing travel time and losing productive (billable) time. Collaborating via videoconference allows law firms to:

- Conduct long distance depositions and other communication for legal procedures

- Stream audio, video, text, and evidence for trials, jury research, and othe litigation uses

- Communicate with distant corporate clients (many of whom use video conferencing regularly)

- Hold inexpensive firm-wide meetings with staff in different locations

- Increase the number of face-to-face client sessions

Videoconferencing space planning has specific requirements

- The space most likely will be used for other meetings besides videoconferencing. Conference and meeting spaces are doubling as project rooms, collaboration spaces, mock courtrooms, etc. Since a videoconferencing space may be used for other kinds of group work, plan the space so that all of the elements – layout, furniture, and work tools – support a collaborative work process.

- The space must support group needs for technology and presentation support, and information sharing. Laptops and PDAs are the tools of choice for knowledge workers –and more legal professionals. Power and data must be easily available.

Furniture systems with new technology interfaces let users quickly display and share information between multiple digital devices. Pair them with seating designed specifically for active collaboration. - The videoconferencing space should support the professional image of the firm. each interaction with the firm makes a brand statement. A professional and well designed space, with high performance furniture and engaging surface materials, sends the right message to everyone in a videoconference.

- A small, economical space for a one-or two-person video exchange may be all that’s required. A portion of a partner office or a small enclave can host a simple one-camera videoconferencing system. Provide a collaborative work surface where groups can spread out materials, a wall or panel-mounted storage unit to support the technology, and task chairs for long-term support.

Partner offices demonstrate the classic knowledge worker need for zones for different work modes. The partner needs to protect confidential information yet needs space to discuss cases with peers and subordinates. The continuing emphasis on paper and at-a-glance visibility of materials drives a need for easily-accessed storage and maximum horizontal work surface.

These same workspace requirements make the partner office a usable workspace when the partner is out of the office. When confidential materials can be easily stored in one zone, it frees up space an associate or legal assistant can use for a period of time.

Storage strategies for law firms include:

- Planning upper and lower storage with appropriate depth and width for legal papers, folders, and boxes

- Providing open storage to provide visual cues and help workers prioritize and organize workload. (The firm’s back office image is less an issue today: external visitors are met in collaborative spaces and meeting rooms more often than in lawyers’ offices.)

- Preferring shelving over drawer solutions, to provide quick accessibility.

Law firms were not early adopters of technology, but Steelcase researchers say they are now steadily adopting these tools. For example, 76% of users have 6 or more electronic devices at their desk, and each person may require up to 6 power outlets and 4 uSB connections. Monitors, on average, are getting bigger and there’s more use of second monitors. Dictaphones are still used in some firms, while some legal professionals are using digital voice recorders. And in this paper-reliant industry, scanners, labeling devices, and personal printers are very common. For heavy technology users such as associates and administrative workers, the computer should take center stage in their workspace. Peripheral equipment that is shared, like printers, should be located outside of their space to free up worksurface area and improve access. Partners usually work with a computer on a secondary work surface, although it’s a less than ideal arrangement because these worksurfaces are usually narrow and short.

A law firm can be an extremely demanding workplace, and as more lawyers seek a better work/life balance, workplace planners should make it a priority to provide more personal and supportive workspaces. Design strategies include:

- Ergonomic task chairs for workers who often put in 12-hour days (upholstered backs not only add to the aesthetic but also prevent marring of the wood furniture often used in law firms)

- Alternative posture options, in particular for paralegals and associates who often sit for long periods

- Zones in the workstation for different work modes, from focused to collaborative

- A means for controlling visual access and entry to the workspace, so workers can maintain information confidentiality

- Providing for personal comfort, which can range from workspace storage for food or a change of clothes to space for family photos and professional artifacts

A new precedent

The legal industry is nothing if not conservative, always seeking a precedent for any activity or change. This approach has often directed their workplace choices as well. But now the industry is dramatically changing how it operates, tackling social and economic changes head-on. It’s adopting new technologies, reconsidering its real estate strategies, and revising its work processes at a faster pace than perhaps any time in its history. Law firms need what for many of them is a new precedent, a dramatically different workplace environment that will meet the demands of clients, staff, and a global marketplace.

References

- Trends in Graduate employment (1985- 2008), The Association for Legal Career Professionals, www.nalp.org, accessed November 19, 2009

- Legal services industry trends, www.hoovers.com/business-services/legal- services/industry_trends, accessed August 3, 2009

- “Best firms for work-life balance” by Karen Dybis, The National Jurist, www.nation- aljurist.com, accessed August 12, 2009

- “economy Pinches the Billable Hour at Law Firms,” The New York Times DealBook, edited by Andrew Ross Sorkin, January 30, 2009

- Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2008-09 edition, Bureau of Labor Statistics, u.S. Department of Labor.

- “Lessons of The Am Law 100” by Aric Press and John O’Connor, The American Lawyer, May 1, 2009, www.law.com/jsp/tal/PubAr- ticleTAL.jsp?id=1202430183962, accessed September 24, 2009

- “The Lateral Lawyer -Why They Leave and What May Make Them Stay” benchmark study by The NALP Foundation for Law Career Research and education.

- Legal Services research report, First Research Inc., August 10, 2009

- Zap Data, cited in the Legal Marketing News, February, 2008

- Occupational Outlook Handbook

- “Law School Debt Among New Lawyers,” by Gita Z. Wilder, 2007, The NALP Foundation for Law Career Research and education and the National Association for Law Placement, Inc.

- ABA Legal Technology Survey Report, as reported by InsideLegal.com, May 12, 2009

- ABA Journal, American Bar Association, “Web 2.0 Still a No-go,” by edward A. Adams, September, 2008

June 2010